Introduction to the Income Statement

At its most basic level, the

Income Statement lists a firm's

Revenue, operating and other expenses, and how much money was left over in some

currency during a specific period of time. This simplicity makes the Income Statement the most intuitive of the

accounting tables in a

financial report.

The Income Statement typically covers a three-month

fiscal quarter or a

fiscal year.

To facilitate comparisons, a quarterly Income Statement will show, side

by side, data for the designated quarter and for the year-earlier

period. Annual Income Statements will list results for two or three

consecutive years.

The bottom-line figure, which is called either

Net Income

or Net Earnings, is expressed both in absolute terms (dollars, or

another currency) and in an amount related the number of common shares

the company has outstanding (dollars per share).

Earnings Per Share gets the most attention in the financial press.

Assumptions

made by corporate management can have a great effect on the Income

Statement's figures. Earnings, which might appear to be the result of

mere arithmetic, are more subjective that it might appear.

Revenue

The

"top-line" of the Income Statement lists the company's Revenue, or

Sales, during the quarter or year. The notes accompanying the financial

statements will indicate what rules the company followed to recognize a

transaction as Revenue. The rules will address questions such as: what

if the company sells an item to wholesaler that can return the item if

it is not bought by a consumer? What if the company receives funds for a

service or product it will deliver in the future.

Determining Revenue is more complicated than counting the cash in the till each day.

Operating Costs or Expenses and Operating Income

The

next section of the Income Statement lists the expenses that can be

tied, directly or indirectly, to the creation and sales of the company's

products.

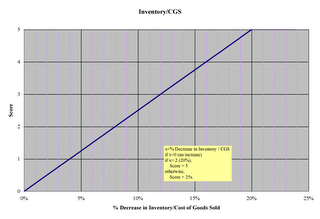

The

Cost of Goods Sold (CGS)

(a/k/a Cost of Revenues) includes the labor and material costs to

create the company's products. It is usually the largest Operating

Expense.

Depreciation of the equipment and facilities used for company operations might be included in

CGS,

or it might be broken out separately. This non-cash expense reflects

decreasing value over time of the company's capital equipment.

Other typical operating expense categories are

Research and Development (R&D);

Sales (i.e., marketing), General and Administrative (SG&A); and

non-recurring Special Operating Charges (less frequently Gains). The markdown (or write-down) of the value of

Inventory is an example of a special charge. This is one example of an

Asset being recognized as

impaired.

Operating Income is found by subtracting Operating Costs/Expenses from Revenue.

Non-Operating Income and Expense

Non-operating

items might include categories such as Gains or Losses on Investments,

Gains or Losses on Asset Sales, Net Interest Income or Expense, and the

catchall miscellaneous category.

The company's Pre-tax Income, or

Taxable Income, is determined by adding the Non-operating gains to, and subtracting the Non-operating losses from, Operating Income.

A

provision for

Income Taxes reduces Income to the bottom-line figure.

Net Income

Net Income is divided by the number of

Common Shares Outstanding to compute the widely reported

Earnings per Share (EPS).

Sometimes non-recurring gains and losses are excluded from the EPS

values one sees in the newspaper or on TV, so the analyst has to treat

these values with extreme caution.

Income Statement Example

While

most Income Statements have the same general structure, they can differ

substantially in the details. The following is a fictitious example,

which we use below to illustrate what can be learned from the Income

Statement.

GCFR Inc.

(Millions of $) |

| Quarter ending

30 June 2006 | Quarter ending

30 June 2005 | Year ending

30 June 2006 | Year ending

30 June 2005 |

| Revenue |

| 52.2 | 43.9 | 198.1 | 170.0 |

| Op expenses |

|

|

|

|

|

| CGS | (39.1) | (33.0) | (149.1) | (127.1) |

| Depreciation | (1.0) | (1.3) | (4.0) | (3.9) |

| R&D | (2.1) | (1.8) | (8.2) | (6.0) |

| SG&A | (3.2) | (1.7) | (11.1) | (7.1) |

| Other ("Special") | (0.1) | (0.2) | (0.4) | (0.8) |

| Operating Income |

| 6.7 | 5.9 | 25.3 | 25.1 |

| Other income |

|

|

|

|

|

| Gains on asset sales | 0.5 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 3.1 |

| Gains on investments | 2.4 | 1.6 | 9.0 | 5.8 |

| Net Interest and other income | (1.2) | (1.0) | (4.1) | (4.8) |

| Pretax income |

| 8.4 | 7.4 | 32.2 | 29.2 |

| Provisions for Income taxes |

| (2.9) | (2.6) | (12.1) | (11.9) |

| Net Income before adjustments |

| 5.5 | 4.8 | 20.1 | 17.3 |

| Equity income less minority interests | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Discontinued operations and Accounting changes | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Net Income |

| 5.5 | 4.8 | 20.1 | 17.3 |

| Earnings per Share ($/sh) |

| $0.46/sh | $0.41/sh | $1.70/sh | $1.51/sh |

| Shares outstanding (M) |

| 12.00 | 11.60 | 11.82 | 11.43 |

What Can be Learned from the Income Statement?

The Income Statement can reveal a lot about an organization's operations. To gain those insights,

financial analysts

measure the rate of change for key Income Statement items, and they

calculate various ratios using data from the Income Statement, other

financial statements, and the supporting

Notes.

The

importance of any particular ratio depends on the size, type, and

condition of the company being evaluated. Changes in the ratios over

time are often more revealing than the values themselves. It can also

be useful to compare ratios for one company with other firms in the same

industry.

GCFR uses the ratios described below.

Revenue Growth

Changes

in the company's Revenue can be characterized in various ways. To

eliminate seasonal factors, it is common to compare Revenue in one

quarter to Revenue in the same quarter of the previous year.

Less

widely used, sequential quarterly Revenue growth compares Revenue in

the current quarter to Revenue in the immediately preceding quarter.

To

smooth out the trend, we compare Revenue during the previous four

quarters to Revenue during the prior four quarters. We refer to this

growth rate as "

year-over-year" growth or "trailing 4-quarters."

Readers should be aware that there are alternative definitions for

these terms. The year in these calculations will coincide with the

fiscal year only 25 percent of the time.

GCFR Inc.

(Millions of $) | Revenue Growth |

| Quarters ending June 2006 and June 2005 | (52.2 - 43.9)/43.9 = 18.9% |

| Years ending June 2006 and June 2005 | (198.1 - 170.0)/170.0 = 16.5% |

Operating Expenses/Revenue

The

ratio of each Operating Expense item to Revenue shows what the company

spent to realize each sales dollar. We make these calculations for the

current quarter and for the last four quarters. If the company is able

to achieve efficiencies of scale as it increases Revenue, costs as a

percentage of Revenue will drop, and more of each sales dollar will

reach the bottom line as earnings.

We subtract

CGS/Revenue from 1 to determine the

Gross Margin.

Alternatively, this can be expressed as (Revenue- CGS)/Revenue. A high

Gross Margin is preferred, as it indicates that the company can sell

its goods and services for much more than the production cost. We find

it more useful to compare the Gross Margins from year to year, rather

than from quarter to quarter because the data for shorter periods can be

volatile.

For fictional GCFR Inc., using figures from the sample Income Statement above:

GCFR Inc.

(Millions of $) | Gross Margin |

| Quarter ending June 2006 | 1 - (39.1/52.2) = 25.1% |

| Quarter ending June 2005 | 1 - (33.0/43.9) = 24.8% |

| Year ending June 2006 | 1 - (149.1/198.1) = 24.7% |

| Year ending June 2005 | 1 - (127.1/170.0) = 25.2% |

When the data is available, we separately calculate

Depreciation/Revenue,

R&D/Revenue, and

SG&A/Revenue. Depreciation is included in

CGS for some firms, and some firms don't engage in R&D.

As

was mentioned for Gross Margin, we prefer to compare the expense ratios

from year to year, rather than from quarter to quarter. Seemingly

random variations in shorter periods can obscure the underlying trends

and lead to erroneous conclusions.

GCFR Inc.

(Millions of $) | Depreciation/Revenue | R&D/Revenue | SG&A/Revenue |

| Quarter ending June 2006 | 1.0/52.2 = 1.9% | 2.1/52.2 = 4.0% | 3.2/52.2 = 6.1% |

| Quarter ending June 2005 | 1.3/43.9 = 3.0% | 1.8/43.9 = 4.1% | 1.7/43.9 = 3.9% |

| Year ending June 2006 | 4.0/198.1 = 2.0% | 8.2/198.1 = 4.1% | 11.1/198.1 = 5.6% |

| Year ending June 2005 | 3.9/170.0 = 2.3% | 6.0/170.0 = 3.5% | 7.1/170.0 = 4.2% |

Finally, the ratio of total

Operating Expense to Revenue gives an indication of the company's overall profitability.

GCFR Inc.

(Millions of $) | Operating Expense / Revenue |

| Quarter ending June 2006 | (39.1 + 1.0 + 2.1 + 3.2 + 0.1) / 52.2 = 87.2% |

| Quarter ending June 2005 | (33.0 + 1.3 + 1.8 + 1.7 + 0.2) /43.9 = 86.6 % |

| Year ending June 2006 | (149.1 + 4.0 + 8.2 +11.1 + 0.4) / 198.1 = 87.2% |

| Year ending June 2005 | (127.1 + 3.9 + 6.0 + 7.1 + 0.8) / 170.0 = 85.2% |

Operating Income and Net Income Growth

Quarter-over-quarter and year-over-year Income growth rates can be calculated in the same way as Revenue.

GCFR Inc.

(Millions of $) | Operating Income Growth | Net Income Growth |

| Quarters ending June 2006 and June 2005 | (6.8 - 6.1) / 6.1 = 11.5% | (5.5 - 4.8) / 4.8 = 14.6% |

| Years ending June 2006 and June 2005 | (25.3 - 25.1) / 25.1 = 0.8% | (20.1 - 17.3) / 17.3 = 16.2% |

Income Tax Rate

The

ratio of Provisions for Income Taxes to the Income before Taxes should

be checked to see if the tax rate has changed. We've seen companies

trumpet increased earnings that were due primarily to a change in the

tax rate (and had nothing to do with the fundamental functioning of the

business). Because the quarterly data can be quite volatile, the annual

tax rate is better suited for earnings models.

GCFR Inc.

(Millions of $) | Income Tax Rate |

| Quarter ending June 2006 | 2.9/8.4 = 34.5% |

| Quarter ending June 2005 | 2.6/7.4 = 35.1% |

| Year ending June 2006 | 12.1/32.2 = 37.6% |

| Year ending June 2005 | 11.9/29.2 = 40.8% |

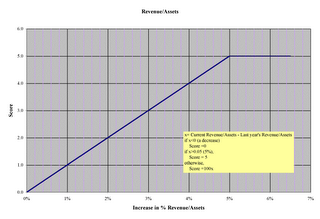

Revenue/Assets

The

ratio of Revenue during a quarter or year to Total Assets indicates how

effectively and efficiently the company is employing its Assets to

generate sales. The key is to look for changes: is the efficiency

increasing or decreasing?

Total Assets is a figure listed on the

Balance Sheet.

When making the Revenue/Assets calculation, the amount of Assets at the

end of the period can be used. However, a more representative

calculation can be made by averaging the Asset values at the beginning

and end of the period. The difference between these two approaches is

more significant for small, rapidly growing companies.

Note

that Revenue/Assets for a quarter will be about 25 percent of

Revenue/Assets for the year. We multiply the quarterly result by 4 to

make it more comparable with annual data. However, this approach can

produce misleading results if sales are highly seasonal. In this case,

an analyst would want to look at historical trends to determine the

typical distribution of Revenue over the year.

Let's assume a series of

Balance Sheets for fictional GCFR Inc. listed the following values for Total Assets:

| Date | Total Assets ($M) |

| 9/30/2004 | 187.7 |

| 12/31/2004 | 192.5 |

| 3/31/2005 | 197.4 |

| 6/30/2005 | 202.5 |

| 9/30/2005 | 207.7 |

| 12/31/2005 | 213.0 |

| 3/31/2006 | 234.0 |

| 6/30/2006 | 255.0 |

We compute Revenue/Assets as shown below:

GCFR Inc.

(Millions of $) | Revenue/Assets |

| Quarter ending June 2006 | 4*52.2/[0.5*(255.0+234.0)] = 85.4% |

| Quarter ending June 2005 | 4*43.9/[0.5*(202.5+197.4)] = 87.8% |

| Year ending June 2006 | 198.1/[0.5*(255.0 +202.5)] = 86.6% |

Operating Profit or Net Operating Profit after Taxes

Operating Profit

is a variation of the Operating Income item on the Income Statement.

We calculate it by excluding unusual operating gains and losses from

Operating Income and adjusting the remainder to reflect Income Taxes.

Operating Profit (a/k/a NOPAT) = (Operating Income + Special Charges) * (1 - Income Tax Rate)

Operating

Profit differs from Net Income in that it excludes Non-Operating income

and expenses, such as interest and investment returns.

At GCFR, we calculate and track

Operating Profit's average annual growth rate

over the last 16 quarters. This growth rate should be less volatile

than the Net Income growth rate because special items are excluded and

the longer averaging time (16 vs. 4 quarters).

Net Operating Profit after Taxes/Revenue

NOPAT/Revenue is a good measure of the profitability of the company's core business.

It would be rare for us to compute this ratio with quarterly values, but we include quarter and annual

NOPAT/Revenue values in the table below to show how the calculation would be made.

GCFR Inc.

(Millions of $) | NOPAT/Revenue |

| Quarter ending June 2006 | (6.7 + 0.1) * (1 - 0.345) / 52.2 = 8.5% |

| Quarter ending June 2005 | (5.9 + 0.2) * (1 - 0.351) / 43.9 = 9.0% |

| Year ending June 2006 | (25.3 + 0.4) * (1 - 0.376) / 198.1 = 8.1% |

| Year ending June 2005 | (25.1 + 0.8) * (1 - 0.408) / 170.0 = 9.0% |

Net Income/Revenue

Net

Income as a percentage of Revenues (a/k/a Net Margin) is a more

complete measure of profitability, but it can be swayed by extraordinary

non-operational changes.

GCFR Inc.

(Millions of $) | Net Income/Revenue |

| Quarter ending June 2006 | 5.5/52.2 = 10.5% |

| Quarter ending June 2005 | 4.8/43.9 = 10.9% |

| Year ending June 2006 | 20.1/198.1 = 10.1% |

| Year ending June 2005 | 17.3/170.0 = 10.2% |

Net income/Stockholders' Equity

This

a basic return-on-investment ratio. Stockholders have a right to

expect that the company will make more for each dollar of investment

than lower risk securities.

Stockholders' (or Shareholders') Equity is listed on the

Balance Sheet.

When making the Net Income/Equity calculation, the Equity at the end of

the period can be used. However, a more representative calculation can

be made by averaging the Equity values at the beginning and end of the

period. The difference between these two approaches is more significant

for small, rapidly growing companies.

Note that Net

Income/Equity for a quarter will be about 25 percent of Net

Income/Equity for the year. We multiply the quarterly result by 4 to

make it more comparable with annual data. However, this approach can

produce misleading results if Net Income is highly seasonal. In this

case, an analyst would want to look at historical trends to determine

the typical distribution of Net Income over the year.

Let's assume a series of

Balance Sheets for fictional GCFR Inc. listed the following values for Stockholders Equity:

| Date | Stockholders Equity ($M) |

| 9/30/2004 | 94.3 |

| 12/31/2004 | 96.7 |

| 3/31/2005 | 99.2 |

| 6/30/2005 | 101.7 |

| 9/30/2005 | 104.3 |

| 12/31/2005 | 107.0 |

| 3/31/2006 | 120.5 |

| 6/30/2006 | 134.0 |

We compute Net Income/Equity as shown below:

GCFR Inc.

(Millions of $) | Net Income/Equity |

| Quarter ending June 2006 | 4*5.5/[0.5*(134.0+120.5)] = 17.3% |

| Quarter ending June 2005 | 4*4.8/[0.5*(101.7+99.2)] = 19.1% |

| Year ending June 2006 | 20.1/[0.5*(134.0+101.7)] = 17.1% |

Return on Invested Capital (ROIC)

ROIC

is a more subtle return-on-investment ratio that provides insight into

how much the company earns on each dollar of capital provided by

shareholders and lenders. We use

NOPAT for the last four quarters as the numerator, and

Invested Capital, which we discussed in the

Balance Sheet tutorial, as the denominator.

From the

NOPAT/Revenue

discussion above, we can determine that the fictional GCFR Inc. had a

4-quarter NOPAT of (25.3 + 0.4) * (1 - 0.376) = $16.0 million as of 30

June 2006.

Invested Capital measures the investment,

whether raised by stock sales or taking on debt, that is actually

deployed (i.e., not sitting in the bank). The definition for this term

that we use is Stockholders' Equity, plus Short- and Long-Term Debt,

minus Cash as the denominator. These values are listed on the Balance

Sheet.

Note:

This post was originally published on 25 October 2006. It was revised

on 1 September 2008, 17 January 2009, 19 April 2009, 10 July 2010, and 4

August 2010.